Drought and the Deschutes: Looking at the same river twice

During this time of year, you can visit the Deschutes twice on the same day and see two very different rivers.

On Saturday, May 1, we took a trip to Benham Falls and caught the river just south of Bend. Later that day, we walked through the Riley Ranch Wildlife Preserve, on the north edge of town, to find a much different river.

Click the video above to hear the sound of the river at Benham Falls.

Last week, Deschutes River flows near Benham Falls were recorded at 1,240 cubic feet per second.

As the river flows through Bend, multiple irrigation channels divert water. Only 5% of the river remains by the time the river makes its way out of town.

Click the video above to hear the sound of the river near Riley Ranch.

In certain areas past the irrigation diversions, only 62 cubic feet per second remain in the river. This photo, taken at Riley Ranch, reveals a much different river.

Drought across the region

Across Central Oregon, we are hearing the rumblings about a drought summer and concern over water shortages for farmers.

While snowpack in the Central Cascades was normal this year, rainfall this spring has been practically non-existent. Precipitation has been well below average while temperatures have been above average.

Over the past 20 years, we’ve seen our region become much dryer. Since 2000, the region’s precipitation has been increasingly below average.

Click here to view a larger version. Blue indicates monthly average precipitation. Red indicates cumulative average precipitation. Source: Oregon Water Resources Department

When water availability declines, what happens?

One thing is clear. The burden of drought is not shared equally.

Oregon’s system for water management was established 120 years ago, creating a priority system for who gets access to water and how much. This system has led to vast inequities in access to water and corresponding social, economic, and environmental impacts.

When drought hits, we often get an oversimplified version of the story. We hear about farmers fallowing their fields, cities unable to serve their residents, and both fall subject to draconian water shut-offs.

The real story is a bit more complex. Rarely do we focus on the nuance of the effects on farmers and cities - some who bear the brunt of the scarcity while others continue to use water without restriction. We don’t often learn about the devastating effects on fish and wildlife.

And worse, the very regulations meant to protect river ecosystems are often blamed for causing the problem.

A closer look at water distribution in Central Oregon reveals a different story.

Where does our water go?

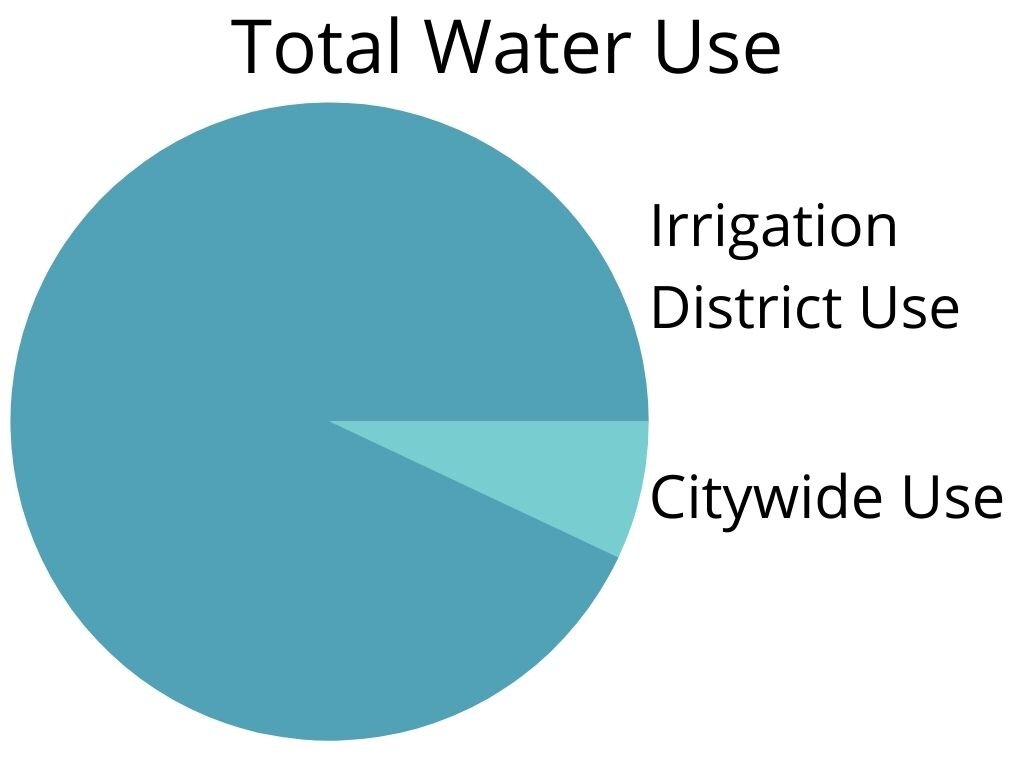

Diversions by irrigation districts dwarf all other uses of water. Of the approximately 750,000 acre feet of water used per year, irrigation districts use 700,000 acre feet.

All of the cities in Central Oregon combined use 50,000 acre feet.

That means, we use 7% for cities and 93% for irrigation districts.

But not all irrigation districts are treated the same. Some receive plentiful water supplies, even during severe drought, and others get barely enough to survive.

The distribution of water among irrigation districts is stuck in a system that was developed in the 1800s and is incapable of meeting today’s needs.

For example, this year, Jefferson County’s North Unit Irrigation District (NUID) will receive as little as 25% of the water that will be available to Deschutes County’s Central Oregon Irrigation District (COID) irrigators.

If water were distributed according to real farming demand and economic productivity, that distribution would be reversed.

Jefferson County, NUID’s home, generates nearly $100 million annually in net farm income. whereas Deschutes County, COID’s home, accounts for a negative net farm income of $25 million, according to the USDA 2017 Census of Agriculture.

In the irrigation community, all water users are not farmers, there are the haves and the have-nots, and the current water distribution causes social and economic hardship for the have-nots.

Irrigation uses

The amount of water used by COID and other irrigation districts in Deschutes County represents large-scale waste. Why is this allowed?

There are two reasons. First, the 19th-century doctrine of prior appropriation dictates that the first person to get water rights has the first claim on the water in the river. This means whoever came first receives the most water, despite the agricultural needs of the land.

Second, while Oregon law says that water right holders must put their water rights to beneficial use without waste, the state lacks a clear, modern definition of “waste” and allows excessive and non-productive use of water to continue. That means there is no incentive for irrigators with senior priority rights to reduce water waste.

In Central Oregon, we have the perfect storm. Water is dumped on tens of thousands of acres with little or no agricultural output because there are no incentives to improve water efficiency.

On the other hand, highly efficient and productive agricultural lands get severely squeezed and are unable to get an adequate water supply.

While all this competition for water among water users is happening, the biggest victim of our obsolete water management practices is the river.

The river seldom gets the water it needs to support fish and wildlife.

What’s left for wildlife?

As seen in the photos above, Benham Falls flows were recorded at 1,240 cfs, but by the time all the irrigation districts had diverted water, only 5% of the flow or 62 cfs remained in the river.

If you want to witness this phenomenon, go have a drink on the patio behind The Riverhouse hotel and behold the trickle of a creek that is a mighty river less than a mile upstream.

The dewatering of the Deschutes River happens every Spring. It is devastating to the plants and animals that depend on it. The food chain is badly disrupted. The insects favored by fish disappear and the fish upon which the otters and osprey depend are greatly reduced. Because of the shallow water, water temperatures spike to lethal levels for fish. The once biologically rich Deschutes River barely survives.

That is why we will continue to work tirelessly to restore the Deschutes River and ensure water equity for our farmers, our fish, and our future generations.