Practice Conifer Identification this Winter

By Lace Thornberg, Communications Director

Is it a Pine, Fir, or Spruce? Let’s find out.

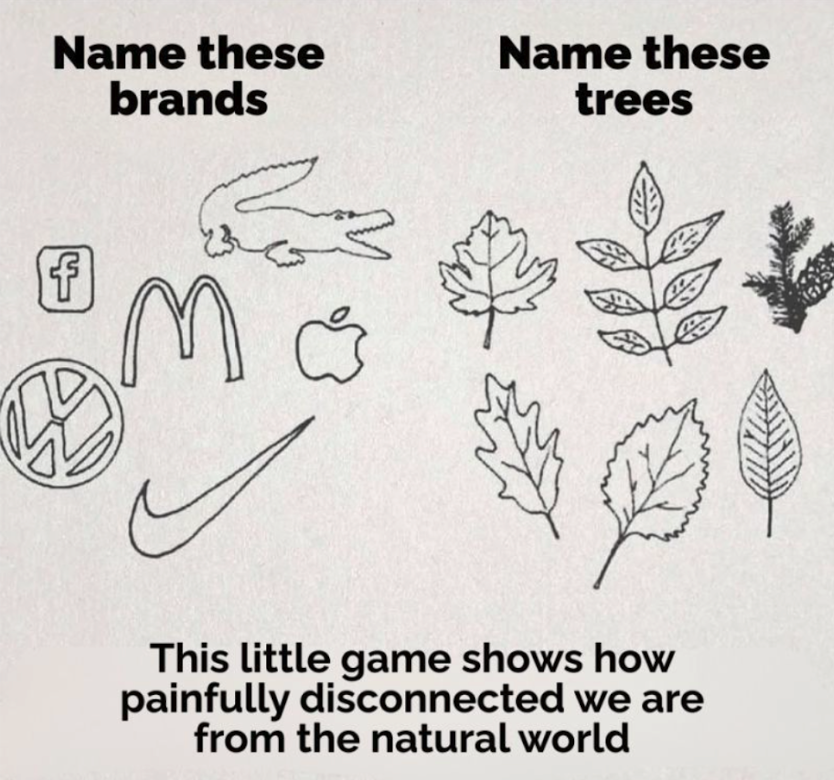

How many trees can you identify by their leaf?

A few weeks back, a “brands vs. trees” graphic caught my attention and I played along. Naming the logos came easily, and I quickly identified six out of six logos correctly. Then came the leaves and needles, and my brows furrowed. Just what tree does that smooth-edged leaf represent? Is that maybe an elm, or maybe an aspen? My heart sank. I am far too ashamed to admit just how poorly I fared, but suffice to say my low score has troubled me since.

When author Richard Louv sounded the alarm about the decreasing connection to nature with his book Last Child in the Woods in 2005, the world took note. Many institutions and agencies developed a slew of interventions designed to restore that connection. Of course, it’s not just kids whose nature appreciation skills are fading. As my low tree score indicates, it’s a problem adults face, too.

With the season of resolutions upon us, getting in tune with the natural world may be on your list, too, and winter is a perfect time to practice evergreen identification.

Out of the 30 conifer species native to Oregon, you can find more than a dozen different species in the forests that make Central Oregon so beautiful to live, work, and recreate in.

The first step to correctly identifying a conifer is to consider your location. For mature trees, considering the tree’s overall height, growth habit and bark will help you narrow in on the species. For younger trees, you can look closely at the needles, and cones to help identify what you’re seeing.

In the high desert stretches of Central Oregon, one member of the Cypress family is particularly abundant: the Western Juniper.

Western juniper

(Juniperus occidentalis)

A 30 to 100 feet tall tree with a massive, squat trunk and large, wide-spreading branches.

Needles: small green scales.

Bark: reddish-brown, shreddy.

Cones: distinctive small bluish berries.

You'll also find a great deal of two Pine family members: Ponderosa Pine and Lodgepole Pine.

Ponderosa pine

(Pinus ponderosa)

Dominating many lower elevation forests in Central and Eastern Oregon, they're highly resistant to fire and can live for hundreds of years.

Needles: 5 to 10 inches long in bundles of three (rarely two, tufted near the ends of branches.

Bark: yellow-tan-rust or cinnamon color, with scaly plates and irregular, deep furrows, pieces break off in jigsaw puzzle shapes. Distinctly candy-scented in late summer.

Cones: three to six inches long and two inches wide with sharp points on the ends of the scales.

Lodgepole pine

(Pinus contorta)

This pine has the widest range of environmental tolerance of any conifer in North America, and grows in areas with cold, wet winters and warm, dry summers.

Needles: Occur in pairs, one to two-and-a-half inches long with sharp ends.

Bark: thin and scaly, orange-brown to gray.

Cones: vary in shape from short and cylindrical to egg-shaped, one-and-a-half to two-and-a-half inches long with sharp, flat scales on the ends, often occurring in clusters.

As you travel into the region’s mountains, you’ll find several more Pine family members, including Grand Fir, Douglas Fir, and Englemann Spruce.

Grand Fir

(Abies grandis)

Found across Eastern Oregon forests, Grand Firs are known for their tall, straight trunks. Biologists have found that their relatively soft wood creates ideal wildlife habitat by providing natural hollows and cavities that wildlife use for nesting, and foraging.

Needles: glossy dark green long needles borne horizontally on opposite sides of the twigs.

Bark: smooth bark on young twigs and small, round leaf scars left by dropped needles. Older branches may have “blisters” filled with resin; pro tip for survivalists: this resin makes a great firestarter.

Cones: Upright in tree tops. Mature cones shed their scales while on the tree, making it rare to ever see an intact fir cone on the ground.

Douglas-fir

(Pseudotsuga menziesii)

Commonly found in the Deschutes and Ochoco National Forests.

Needles: flat, roughly 1 inch long, single on the twig, narrowing before they join it, the same color on both sides, soft to the touch and very fragrant.

Needle tips: blunt or slightly rounded.

Bark: thick and reddish, deeply furrowed on mature trees.

Cones: the only cones in the Pacific Northwest with a papery, trident-shaped “tail” sticking out from under each scale. (Imagine a mouse scurrying for cover, with its butt hanging out.)

Engelmann Spruce

(Picea engelmannii)

Thrives in high-elevation areas of the Fremont-Winema, Deschutes and Ochoco National Forests, often growing in moist, cool environments.

Needles: dense, blue-green

Bark: thin, flaky.

Cones: Pendulous; male cones are small and dark purple and the light brown female (seed) cones cluster near tree tops.

Knowing more about the tree species that surround us helps ground us in the place we call home and be good stewards of all inhabitants.

Photo Credits:

Western Juniper: Wasim Muklashy

Ponderosa Pine: Wasim Muklashy

Lodgepole Pine: USDA

Grand Fir: Rob Klavins

Douglas Fir: Gerald and Buff Corsi, California Academy of Sciences

Engelmann Spruce: Susan McDougal, USDA